Are you writing about a plague doctor in your medieval or time travel novel?

You’ve come to a good place. No plague here other than the occasional grammar mistake.

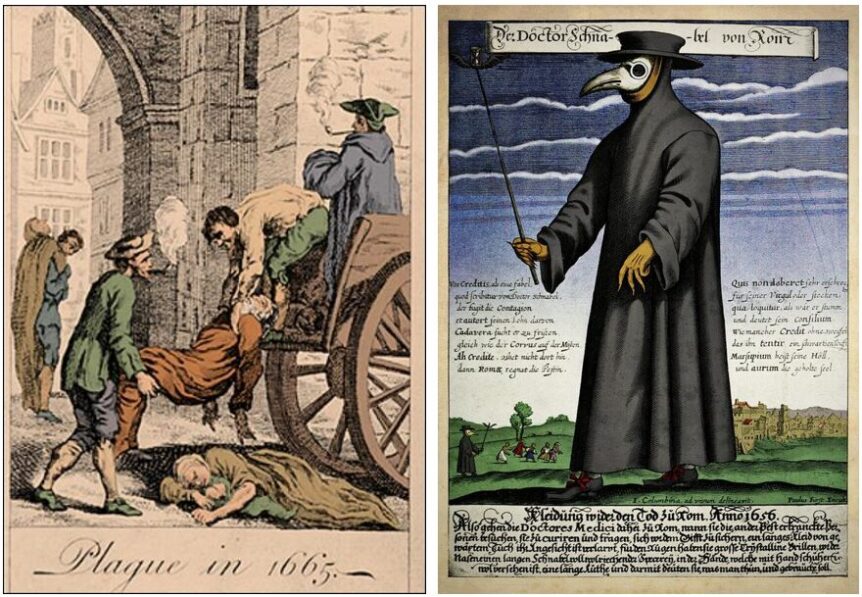

I’ve always been fascinated by these medieval plague outfits. Is there any more chilling image of a doctor than this? Macabre, to say the least.

Give me a Norman Rockwell family physician any day!

So, here’s what a writer needs to know about these scary medical figures.

First: A Black Plague Primer

If you plan to write about a plague doctor, one needs to know something about the Black Plague. The bubonic plague is caused by a bacterium called Yersinia Pestis, discovered in 1894. Carried by infected rats (who lived among humans and then died of the plague), it was then transmitted by flea bites to other rats or fleas to humans.

Highly treatable today with antibiotics, in the Middle Ages it was deadly. The average mortality was 60% among all ages, races, nations, and social classes.

The plague takes three forms. They’re different in how they present, how they’re spread, and their mortality rates.

1. Bubonic (from which it gets its name): Caught from a flea bit or handling infected materials like clothing, this is the most survivable form. It’s known for large infected swellings called buboes. Buboes are enlarged lymph nodes (egg-sized) trying to drain the infection and dead cells from the body. Incubation period is 2-6 days.

Bubonic type presents with:

- sudden high fever and chills

- pain in arms, legs and belly

- headaches

- nausea and vomiting

- buboes develop

- Four of five (80%) would die within eight days.

- Buboes could be quite painful, and last for weeks. Often required drainage or lancing of the pus.

2. Pneumonic: This form is the most contagious. It’s either pneumonia that develops from infection spread from a buboe, or its caught by inhaling infected droplets of saliva or mucus coughed out into the air from the infected lungs of another person (today called ‘primary inhalational pneumonic plague’).

This is NOT the same as an “airborne” virus like Covid, where the virus can hang in the air for hours and doesn’t need mucus or fluid to travel on. Even with modern day treatment and antibiotics, the pneumonic form of plague is hard to survive and has only a 50% chance of survival.

- Mortality of pneumonic plague is basically 95-100%. A very rare few survived.

- Incubation is 1-4 days

- Fatal withing 18-24 hours.

- Presents with high fever (102F degrees or higher)

- Cough, chest pain, shortness of breath

- May cough up blood

- May develop buboes

3. Septicemic: This form is the kind people might have and not been aware they were sick, walked off a ship onto the docks, and dropped dead. Septicemic plague means the bacterium has overwhelmed the person’s immune system. This happens when a flea manages to bite into a blood vessel, or the infection spreads rapidly from a buboe.

- Presents with diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, fever, shock, weakness

- 100% fatal in the Middle Ages

- NO Buboe usually

- Rapid onset, within hours

- Multi-organ failure

- Peripheral (in the extremities) gangrene

- Profound hypotension- low blood pressure

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, called DIC (not known in Middle Ages)

- Death usually from cardiac arrest

What was a Plague Doctor?

Multiple waves of the Black Death, or “the Great Mortality,” as it was called at the time, occurred over the centuries since the Roman Empire disintegrated. The cycle seemed to be around six to ten years. Most doctors, I’m sad to say, fled infected areas. In fact, so many left, cities and towns of the period needed a solution to treat the sick and dying.

They came up with the idea of the “Medico della Peste” or plague doctor. Plague doctors were hired by the local government and assigned various areas of the city or countryside, much like the parish system in the Catholic Church. While they were supposed to be an actual physician, not all were trained doctors. Some were barbers, or medical students. Others were complete fakes.

Plague doctors weren’t the “treating physician” per se, who tried to cure the patient. A regular doctor could still see and care for the patient. The plague doctor got their reputation because they showed up at the last.

Their Function?

A plague doctor’s primary job was to register new infections and document deaths. This makes them the first official epidemiologists. They were also tasked with seeing to the proper disposition of bodies, suggesting treatments, and even the witnessing and recording of wills.

Since they were paid by the government, both poor and rich alike were treated free of charge. Wealthy citizens often paid extra, though – if the plague doctor had a salve or medicine or treatment that could be tried.

Plague doctors could perform some treatments, but it was aimed at comfort not cure, like a modern hospice physician. By the time a plague doctor got called to the house, the patient was on their way out. While the plague doctor could suggest some rather bizarre treatments (like putting toads on buboes — the infected lymph nodes), or attaching leeches for bloodletting– which might have been of some benefit for severe swelling, the plague doctor could lance a painful bubo.

Galen’s Theory of the Four Humors was still held to be gospel, so they followed his ancient and mostly impractical advice. Some of the treatments are downright diabolical, like drinking one’s own urine or applying dung to a wound depending on one’s diagnosed “temper.” As is today, some doctors were better than others and realized they weren’t helping and tried something new. Like tincture of opium for excruciating pain.

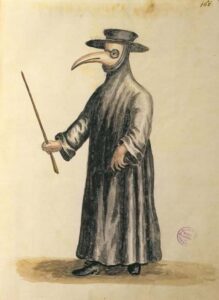

Venetian Plague Doctor with a white beaked mask

Venetian Plague Doctor with a white beaked mask

Why the Plague Doctor costume?

The prevailing opinion was that bad air, called “miasma,” transmitted the plague and could be combatted with sweet smells and avoidance of contact with air in the room of a plague patient. Plague doctors were advised to wash their hands and any exposed skin with vinegar, which is a mild acid and would do some good to remove germs.

As early as 1373, a beaked plague mask worn by physicians is referred to in the writing of Johannes Jacobi. When plague hit Paris again in 1619, the renowned physician, Charles de Lorme, was called upon to treat the French king Louis XIII and his court, along with Cardinal Richelieu.

De Lorme devised a “plague preventive costume” and his biographer described it in details which were recorded by a historian. De Lorme’s costume was the first true hazmat suit, or personal protective gear. A neck-to-ankle leather or linen garment was covered in suet and flower petals or perfumed herbs to drive the bad smells away. A leather undergarment of pants was then tucked into leather boots or shoes. The doctor’s leather hat identifies him as a physician, and its wide brim may have shielded against spittle. Some think it looked more like an old-time long underwear suit.

The mask is most striking. Made of goat leather and waxed, it strapped on the head to seal the face. Later models added glass eye lenses so the doctor could see. The long beak or cone was packed with good-smelling stuff – again to fight bad smells. It could contain any number of materials:

- Ambergris

- Laudanum

- Mint

- Camphor

- Straw

- Moss

- Myrrh

- Rose petals

- Theriac – an ancient mix of 55 ingredients used since Roman times including herbs and spices (not used for fried chicken)

My guess it started out as a leather or metal cone, and a mask maker may have made it look more like a beak. Or the beak mask illustrations were just that – an illustration and not accurate.

Leather gloves were a must. The gloves at least in one drawing (which was a book cover to a satire on plague doctors) appear to have claw-like fingertips, for reasons unknown. It may be the satirist wanted the doctor to look more threatening. I surmise it was another way to distance from the infected patient, to poke and examine buboes and other swellings. Or perhaps they lanced the buboes with them? This would protect the doctor only so long as those gloves were either washed or replaced each time.

The doctor’s cane served a vital function. It was used as a pointer to direct helpers, to examine the patient, move infected clothing around or off the patient, and keep away any undesirable close physical encounters with a sick patient who might try to grab the doctor.

While these medieval physicians were correct about something contagious being in the air, they were wrong about what it was. It certainly was not bad smells.

Unfortunately, the two air holes of the plague mask were near the wearer’s nose

and allowed direct inhalation of germs –

the air wasn’t filtered through the herbs mix which might have actually helped.

It is thought that the leather garments protected them from fluids and fleas, so it was of some benefit.

FYI the plague doctor outfit in my video wasn’t illustrated until 1656 – that is taken from a German woodcut by Gerhart Altzenbach. An

earlier printed version came from Italy, done off of a copper engraving.

And the mask didn’t have holes along the edge – that’s the modern Steampunk design of my mask.

The gloves in this 17th C. costume are more likely – they resemble modern leather gardening or heavy-duty work gloves.

They would wear another garment under the gown with pants that tucked into footgear.

Who worked as Plague Doctors?

- DeLorme was a famous court physician with a good record of treating his patients.

- The most well-known name to have served as a plague doctor was probably Nostradamus.

- At least two female physicians were recorded hired as plague doctors in southern Italy. Female doctors were usually the daughter of a doctor who had trained them.

- Many plague doctors were total fakes and cheated patients by making themselves the recipient of the wills.

- While Jews were suffering pogroms and blamed in many districts for “poisoning the wells” with plague, there were Jewish plague doctors. Female Jewish doctors are noted to have worked in southern Italy and Sicily.

The Perks of Being a Plague Doctor

- Could command 200 florins a year, four times a doctor’s regular salary

- Free housing and upkeep

- Most were highly respected

- Could be granted citizenship in the town or locale

- Allowed to do autopsies, which were often illegal or forbidden by Church officials

The Downsides of Plague Doctoring

- Catching the Plague and/or dying

- Restricted Travel – could not move about town without an official escort

- Lonely life – could not live near others

- Some were kidnapped and held for ransom

Don't use plague doctor costumes in an English setting. Share on X

Of note – No plague doctor costumes like these are recorded being used in England or the UK. I’ve seen at least one mistaken use of this in a film.

(Now, if you have a French doctor coming to treat the English king, that could work!)

Research Suggestions for Writing about Plague Doctors:

John Hatcher, “The Black Death: A Personal History” https://tinyurl.com/2s4ev6pu

John Kelly, “The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time” https://tinyurl.com/34p394wt

Giovanni Boccaccio, “The Decameron” Fictional set of stories, but written in the 14thC. and considered an authentic resource. Free versions can be found online or print translations on bookseller sites.

Robert Gottfried, “The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe” https://www.amazon.com/Black-Death-Natural-Disaster-Medieval/dp/0029126304/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Philip Ziegler, “The Black Death” https://tinyurl.com/2edu885d

If you have the time and money: Dorsey Armstrong, PhD’s, “Great Courses Series” on video is fabulous. “The Black Death: The World’s Most Devastating Plague” Also available on Amazon Prime video. https://tinyurl.com/yuy6963s

https://www.britannica.com/event/Black-Death/Effects-and-significance

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549855/

Austrian or German 17th-century plague doctor mask on display in Berlin’s Deutsches Historisches Museum

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4a/17._Jht._Pesthaube_anagoria.JPG